This picks up where I left off in my last writing. In the greenhouse, sweat dripping from every pore of my body, soaking through my clothes. I had finally entered the den of spiders. All spring and summer, I’d let a legion of large spiders live in the greenhouse. Not so much out of generosity, but out of reluctance to face them.

Despite my fear, spiders have been capturing my attention ever since we moved onto this land. It’s spider season for me, and this is how I know.

I also know I’m alone in my fear, or at least repulsion, of spiders. Most people are, and yet why? Of all the 5,000 types of spiders on this planet, only a few are dangerous to humans. Spiders avoid us at all costs and rarely bite unless they feel threatened for their lives. We’re far more dangerous to them than they to us.

Actually, spiders are essential to our survival. They prevent pests from overrunning the planet. Without them, insects would multiply exponentially, ruining vegetation and spreading disease at rapid rates. Spiders play a vital role in keeping our ecosystem in a state of balance. It’s why I don’t mind that a spiderweb gets woven outside of my bedroom window every evening. It means less mosquitos get in to feast on my blood. Even my boys will check to see if their “protector” is there, shielding their window like a screen, enabling them to keep it cracked on a warm summer night.

Where, then, does all of the fear come from? Despite my intellectual understanding of spiders as protective, nurturing and essential to life, why do I find myself squealing like a banshee when confronted with them?

This summer, curiosity has exceeded my fear. I’ve been watching spiders with attentiveness bordering on devoutness. My curiosity also led me to science, to ancient myths, and any stories I could find. Thread by thread, patterns have emerged, disintegrated, been re-spun. I’ve become entangled, disentangled, re-entangled. I had no idea what I was getting myself into when I started this.

You’re in for a fun ride!

“I do, I undo, I redo.”

– Louise Bourgeois

I began by revisiting stories from my childhood, like E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web and even Miss Spider in James and the Giant Peach. In both, I found benevolent, nurturing, mother-like spiders who were sympathetic, life-saving companions. Charlotte is just a common gray spider who reminds us that ordinary people can do extraordinary things. And about the power of story. The power, in fact, of a single word when artfully woven. Charlotte uses language to re-write the story of Wilbur, transforming everyone’s perception of him, even his own. Her webs entrap flies, yet free Wilbur’s life.

Later in childhood came Spider-Man. This life-saving, sometimes soul-redeeming, hero is based on Greek myths like Theseus’ journey to defeat the Minotaur. There are plenty of superheroes in Greek mythology though. You can visit any Homeric epic and find them aplenty. Isn’t every modern superhero simply a retelling of these ancient myths?

In Greek mythology, however, the first Spider wasn’t a male techno superhero. It was a common woman named Arachne.

Like Charlotte, Arachne was virtually powerless in society yet became a highly skilled weaver. Her tapestries were so magnificent that everyone thought she’d been trained by Athena herself. Powerful goddess of war, Athena was also the keeper of arts and crafts. Particularly in weaving and spinning, she was believed to be the divine source of artistic skill.

But Arachne was self-taught and confident in her own abilities. Fatefully, she challenged Athena to a contest. The two women—one a goddess, the other fully mortal—wove their tapestries. Athena’s tapestries told stories about the power of the gods, their victories in war, and their inclination to punish any mortal who challenged them. Arachne’s tapestries told stories about the pettiness of the gods, how they tricked mortals and brutally misused them, often without justification. When their tapestries were done, Athena saw that Arachne’s weaving surpassed her own. She couldn’t find a single flaw in Arachne’s work. This enraged Athena. She was already furious about the stories told in Arachne’s work – a perspective of the gods and goddesses she didn’t want to see. Now she was also confronting the fact that a mere mortal had surpassed her in skill. Blind with rage, Athena destroyed Arachne’s tapestries and beat Arachne over the head. Arachne escaped the beating but then hung herself in shame. The hanging stirred pity in Athena. She turned the rope around Arachne’s neck into silk. Then turned Arachne into a spider. This spared Arachne’s life, yet sentenced her to an eternity of weaving.

Now we are moving out of Charlotte’s benevolent, motherly web into the idea that women become transgressive, even monstrous, for excelling in a way that threatens power structures.

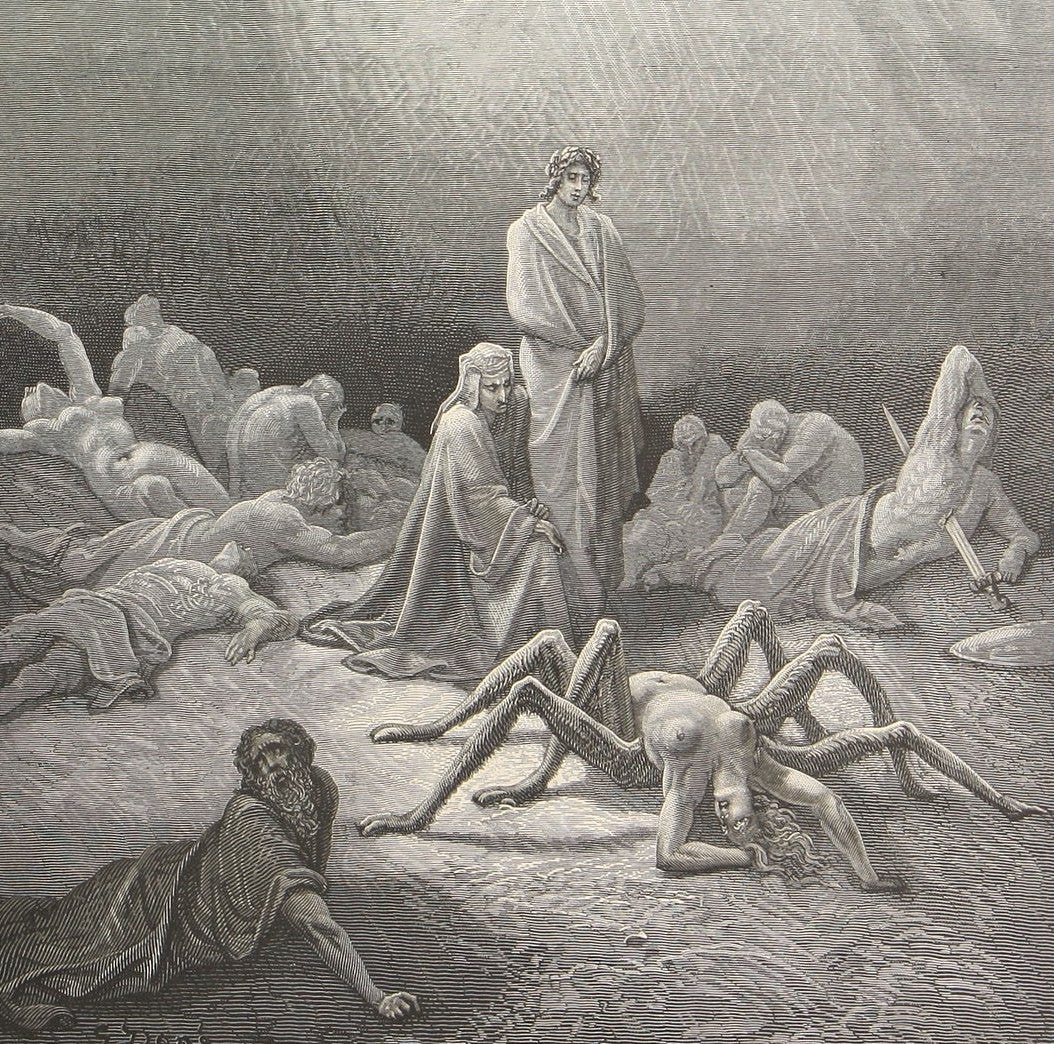

Arachne’s monstrosity landed her in Purgatory of Dante’s Inferno representing the very image of pride itself. Was pride truly her downfall though? Is pride in one’s own creative abilities really such a sin? Considering that Inferno is a Christian text, then yes, pride becomes a great threat in the hierarchical world order of Christianity. Arachne was made an example of what happens to women who become too great or who speak their truth. Athena was also a woman yet belonged to the ruling class and benefited from her status as daughter of Zeus. It was in Athena’s interest to ensure no one, especially a mortal woman, dared strive for equality with the league of gods and goddesses.

Arachne should have stayed small, as that was her place in society. Instead she dared to crawl out of her hiding place and stand proudly in who she truly was – a weaver whose skill exceeded Athena’s. For that, Arachne’s art was destroyed, she was beaten and cursed to her last descendant.

How Spider-Man, also part-human, part-spider, got reinvented as a slick, agile, soul-saving superhero with no sign of monstrosity, I have no idea. That’s 1960s American media for ya. That’s also patriarchy. In 1977, Spider-Woman appeared in the Marvel comic series, yet she “was intended as a one-off character for the sake of simply establishing trademark.”1 People responded so well to Spider-Woman that publishers kept her around, but still, she had very little role in the overall story. Her presence was to prevent other companies from developing her character. In short, Spider-Woman of the Marvel universe was bought, branded, caged, culled.

In Native America there was another Spider Woman. One could say the original Spider Woman. And she played a huge role.

Spider Woman was Earth goddess, the one who first created the world when it was just darkness, chaos and instability. According to myth, the Sun god, Tawa, had a dream one night about many plants and animals. He told Spider Woman about his dream, and she began to fashion them into being. As she wove the world together, patterns of lightness and beauty emerged. There was an innate wisdom in the design - endless connections that held the world in a state of balance and harmony.

Spider Woman used the clay of the earth, red, yellow, white, and black, to create people. To each she attached a thread of her web which came from the doorway at the top of her head. This thread was the gift of creative wisdom.

– from the Diné creation story

This creative wisdom guided the people of Earth. Many Native American cultures – Navajo, Hopi, Pueblo, even as far back as the Mayan people – credit Spider Woman for their ability to understand the interconnectedness of all things. They credit her for protecting them and for gifting them with important skills. Weaving was obviously one of those skills. It was crucial to the function of life and also led to the renown weaving patterns that, after hundreds of thousands of years, remain unrivaled.

Spider Woman was the first to weave. Her techniques and patterns have stood the test of time, or more properly, the test of timelessness – because they’ve always been present.

It makes sense that one would follow the instructions of a deity who helped form the underlying structure of the world in which one lives... Weaving is, from that perspective, not an act in which one creates something oneself – it is an act in which one uncovers a pattern that was already there.

– John Loftin, anthropologist and writer of Hopi culture

Spider Woman feels so relevant today.

I recently listened to a conversation Krista Tippet had with Janine Benyus and Azita Ardakani Walton. They were discussing how nature heals from trauma. From small traumas like cutting one’s finger to huge traumas like Mount St. Helens blowing up, causing an entire ecosystem to collapse. Across all scales, “there are patterns. As Bateson would say, ‘the pattern which connects.’”2 As Native Americans understood it, the pattern that is already there and has always been there.

In the case of Mount St. Helens blowing up, studies show that the first organism to arrive on the scene of that desecrated landscape was, lo and behold, a spider!

In the studies on Mount St. Helens, the first organism that came in that incredible ash field was a ballooning spider. So spiders will put out — when they’re very, very tiny — they’ll put out a long, long, long, long, long silk thread and then let go of wherever they are. And the silk thread gets picked up by the wind and they get carried, way up into the atmosphere…

That was the first organism they found, was a spider. And that spider built a web, probably out of its balloon, and then that attracted other insects that came by. And next thing you know, all of this organic matter started and started to grow. And so did the seed banks. Things came up that were already in the seed bank.

- from On Being’s On Nature's Wisdom for Humanity

This real-life event with scientific data proves the intuitive knowledge Native Americans had about nature and creation. About Spider arriving and beginning to throw out threads. Spider beginning to weave. And from those acts, nature beginning to heal, to grow, evolve and thrive.

I find this fascinating, as it echos Native American knowledge and confirms Spider as a creative force.

I’m beginning to see Spider as the embodiment of the creative process.

Every night, a spider crawls out from under the awning above our back door. It throws out a thread in one direction. And then another in the opposite direction. And another. Until it is weaving within many different points. Slowly, artfully it works. Intertwining. Reinforcing. Its eight legs moving in a way that reminds me of a musician’s fingers. If you watch a great musician, they will almost disappear while playing. It’s as if they’re in service to the music. The music turns them into a channel whereby songs can flow out.

As a writer, I know the feeling. It’s the moments I dream of, live for. When something bigger flows through me. These moments don’t happen often, but when they do, I enter a state of ecstasy. Life has purpose and momentum, and I am in service to it. There is absolutely nothing like it.

And yet how I can struggle with writing. I can overthink and overanalyze. My voice becomes trapped in my mind rather reaching into that deep well of my body. I can compare myself with others. Revert to people pleasing because I fear rejection, or rather, abandonment. I can let everyone else’s needs become more important than my need to write. I can stop showing up to do the work. I can downplay the importance of writing. I can live without writing, right? I can stop being attentive to the world as a writer must be. I can distract myself with jobs and titles, social media consumption and all the social norms of good mothers, good women. “Leg traps” as Clarissa Pinkola Estés calls them.3

Except that writing is something I can’t stop doing, or thinking about doing. Amidst all the noise of modern life, it’s the impulse within. The very pulse of who I am. If I’m not writing, I’m hardly alive.

Spider is sustained by the act of creating. It weaves without knowing if it will catch an insect or not. Because if it doesn’t weave, it doesn’t eat. The careful weaving its web shows its capacity for patience, process, and rhythm. And how embodied it all is. They go about their daily work not because someone has commissioned it, but because it’s who they are. They don't waste time comparing their webs to other spiders' webs either. They just weave. They are in constant practice, in constant process. They mend when they can, and start anew as many times as they need.

Also, spiders use what’s right inside of them, the thing they were born with – threads of silk that, when woven together, become the very thing that serves to sustain them, and to sustain the larger ecosystem in which we all live.

The question is not so much “What do I learn from stories?” as “What stories do I want to live?” The non-dual way to say this is “What stories want to come to life through me?”

– David R. Loy, The World Is Made Of Stories

I’ve never acknowledged the bravery of spiders to crawl out of their dark hiding places and to be fully themselves. To weave between earth and air, sometimes covering vast distances, and when they’re done with their work, to splay themselves out right in the center of it. Of course it would be safer for them to remain in the shadows where predators (birds, frogs, wasps, fearful humans) can’t find them. But that’s not who spiders were designed to be. That’s not the work they’re here to do.

If Spider is a representation of the feminine, and if Spider is a force of balance in the structure of life itself, then perhaps Spider is a glaring reminder that we need the feminine to maintain a healthy balance in the human world too – both in our souls and in our societies.

For the last 6,000 years, we’ve lived in a world where almost all meaning has been constructed by men. In this narrative of modernity and enlightenment, we’ve defeated the wilds. We’ve broken out of the web of life and exist outside of it, pulling threads as we wish. We’re abstractions. Our theories of time, money, power, possession, freedom, they’re all abstractions. We receive very little feedback from the world. We recognize very few life forms, and almost no patterns at all. In fact, those things challenge our narrative. They challenge our sense of identity and reality just as Arachne’s tapestries challenged the gods of ancient Greece, and so we fear it. Whatever we fear, we destroy. We turn it into a monster and ostracize it, allowing our own violence against it to become routine and, yes, monstrous. Which should lead us to question who and what the “monster” truly is.

Is it any coincidence that all the of books written about giant, monstrous spiders have been penned by men? I found a list here. From Dungeons and Dragons to these many Weird Tales, there are many horror stories featuring bloated, voracious, evil spiders who are out to kill the male protagonist. In every tale, the male protagonist finds a weapon of some sort - a gun, an axe, a fireplace poker, etc. - to fight and destroy the spider with. If this isn’t symbolic of the macho techno world we live in and it’s superiority over anything bodily, feminine and instinctual, then I don’t know what it is!

One of the most monstrous spiders portrayed in contemporary mythology is Shelob in Tolkein’s Lord of the Rings. Shelob lives at the threshold of Mordor, and she is voracious. She consumes without ceasing and for virtually no reason. Remaining neutral to the battle going on in the world, it’s as if Shelob is outside the world of reason and morality, confined to her bodily appetite. Shelob was the last descendant of Ungoliant, a dark giant spider who was from “before the world" — some original form of darkness. In Tolkien’s tales, Spiders were associated with pure evil. The “wove webs of shadows.” And they were female.

We’ve come to relate to femininity as grotesque. I see it all the time, in women just as much as men. People so frightened by those “unacceptable” parts within themselves they can’t stand to see it in anyone else. If they see it peeking out, they smash it out of fear, just like we smash spiders when we’re confronted with them. Even though spiders are rarely dangerous, unless they feel endangered. Why would women be dangerous either?

The Dangerous Old Woman, this two-million-year-old woman is qualified, in many cases over-qualified in creating…. This two-million-year-old woman is within the psyche. It’s an ancient way of thinking and being. It has nothing to do with ‘Am I enough?’ It has to do with ‘I AM SO MUCH. WHERE SHALL I START? Where should I put my first mark, and the second, and the one after that?

– Clarissa Pinkola Estés

Where will you attach the first thread? I heard Spider ask as I sat down to write this morning. And the next? And then after that? Keep going, it said. Trust the process.

There are so many other stories. I haven’t even gotten into the work of Louise Bourgeois, whose spider sculptures explored motherhood with metaphors of nurture and protection, yet also something peculiarly monstrous too. Her work asked me to reflect on my own experiences of motherhood - how creaturely it is, how instinctual, and just how much social conditioning I’ve had to unravel in order to stay intact as a woman, mother, and artist.

I could write pages about it. And more pages on the liminality of motherhood. On the liminality of artists. Outsiders. Spinsters. On all of the liminal, un-belonging, un-becoming “others” who have been pushed into the shadows.

Spiders, too, are liminal beings. They weave webs in the air yet anchor them to earth. Webs that are stronger than steel yet as delicate as lace. Webs of incredible artistry made by bodies we find so repulsive. By day, they live in crevices and cracks - places that are dark and scary, and yet as Leonard Cohen wrote, cracks are “where the light gets in.” In many ways, spiders resist our ontological categories. Which we hate! We’re overly attached to stability. Deeply uncomfortable with anything that causes our hierarchies and certainties to dissolve.

It’s right in these liminal spaces, in these cracks, or these thresholds between two opposing ideas that tricksters emerge.

Which could bring me to Anansi, the trickster spider of Western African mythology. Here, for the first time, we see a male spider,4 a shape-shifting figure originating from the Ashanti people in Ghana. Anansi was known to be a real troublemaker, a force of both destruction and yet also liberation. Anansi wanted to rescue all the world’s stories from a dominant sky god who hoarded the stories in large piles around his sky palace.

The sky god said (to Anansi), “Great and powerful towns like Kokofu, Bekwai, Asumengya have come and they were unable to purchase them, and yet you who are but a masterless man, you say you will be able?”

Anansi was indeed powerless. But he was a very cunning spider.

In exchange for the stories, the sky god demanded Onini the python, Osebo the leopard, Mmoatia the fairy, and Mmoboro the hornet. It was an impossible mission. But Anansi was determined to free the stories, to bring them down to humanity. And so, using trickster wisdom, he did the impossible. He took the four captives back to the sky god, who said,

Anansi, from today and going on forever, I present my sky god stories to you, kose! kose! kose! my blessing, my blessing, my blessing! No more shall we call them the sky god stories, but we shall call them the spider stories!

Anansi took the stories and gave them out to all the people on earth, which brought them much joy. These stories never left the people, even when they were captured, sold and put on ships. The spider stories accompanied them on the transatlantic slave trade. They lived on in the Caribbean, in the hearts and souls of West Africans, reminding them who they were and where they came from.

Stories once held captive by an authoritative sky god, then freed by a disruptive spider figure. Stories once trapped, then disentangled from greed, and then re-entangled into the psyches of humans. Stories once stagnant, as if dead, and then alive, in motion, retold in new ways, reconfigured for new times.

This is trickster wisdom for you. It’s spider wisdom. Creative wisdom.

The last story I’ll mention is a Lakota creation myth of the Sioux people, as retold by Michael Meade. In the myth, an old woman in a cave weaves a beautiful, intricate tapestry using porcupine quills, or dry grasses, or even sheep’s wool. The only time she stops weaving is when she goes to the back of her cave to stir a large pot containing seeds or other plant material she uses to dye the fabric of the world. The pot hangs over a fire that’s been going since the beginning of time.

When she leaves her tapestry, two beady eyes watch her from a dark corner. Sometimes it’s a black dog, and other times a trickster crow. As soon as the woman is out of sight, the crow begins to peck at the tapestry, or the dog pulls at it with his teeth. One by one, the fibers unravel. By the time the old woman returns, her tapestry has been completely unraveled. Only a heap of string remains on the floor. But she is not surprised. She simply sits down and begins to weave again. This time she decides to weave a different pattern with different colors. And so a new world is created as the old woman sits in her cave weaving, eons after eons.

The old woman isn’t bothered by the unraveled tapestries, because she knows that the trickster crow (or dog) is keeping life in motion. If she were to finish her tapestry, the world would effectively end. When creation ceases, life ceases. So in the dismantling of one form, new forms can arise.

This life-death-rebirth cycle is inherent in the female body too. We literally embody the cycles of creation. It’s ongoing. Every day we experience a part of the cycle that’s connected to all the old parts and all the new parts to come.5

I see it in Spider too as they spin their webs every evening. Different patterns emerging. Different shapes fit for different places, different times. I see the cycles of life happening within their webs just as it happens in my own body. In webs, in wombs, interconnectedness, interrelatedness, life, death, rebirth, reminders of our ability to undo and redo, over and over again.

There’s always the potential to get too lost in myth. Our ancestors offer a lot of guidance and contemporary artists present new interpretations. But at some point I must give way to my own process with Spider. And so I move forward with an arsenal of stories and scientific facts, myths and spiritual meanings. Yet I also remain a witness to spider activities happening around me. I attune myself to this fascinating creature, follow the threads it weaves right outside of my windows and begin to weave my own meanings.

I know Spider isn’t done with me yet. I know its birthing season now, that mother spiders are nestling egg sacs into small, protective webs. Just the other day I was harvesting peas in the garden when I saw a spider on the underside of a pea leaf. The spider began to move frantically. Then I saw why. She clutched an egg sac with 2 of her legs while using her other 6 legs to weave a tunnel, almost like a portal, thick with silk. When it was complete, she nestled the egg sac into the bottom of the tunnel, and then stood on guard at the entrance. It was so beautiful, so tender. I backed away and wished her well, and all her babies too. May they be kept from harm. May they reach their highest potential. To masterfully stitch and keep life as we know it in balance.

Soon spinderlings will be hatching everywhere. They’ll weave long trails of webs and travel along them like silk highways, looking for warm places to spend the winter. I wonder if I’ll be able to join one or two of them, to follow them away from my home and my garden into those wilder, darker places where new life is nourished.6

I wouldn’t mind it at all.

xx

Beth

ADDITIONAL READING AND LISTENING

https://www.cecklim.com/blog/spider-feminism-arachne-to-arachnology-via-the-web

https://onbeing.org/programs/janine-benyus-and-azita-ardakani-walton-on-natures-wisdom-for-humanity/

https://decoratingdissidence.com/2022/07/01/loom-and-spindle-the-polarising-history-of-weaving/

https://www.sacredartjourneys.com/saj-articles/2013/9/14/encountering-the-wild-woman

https://ecoist.world/blogs/eco-bliss/the-history-of-weaving-and-women

https://feathersandfolktales.com/diemdangersblogposts/the-weaver

In Women Who Run with the Wolves, Clarissa Pinkola Estés defines leg traps as “various lures to which we are susceptible: relationships, people, and ventures that are tempting, but inside that good-looking bait is something sharpened to a point, something that kills our spirit as soon as we bite into it."

Men contain feminine energy too! Just as women contain varying levels of masculinity. We all have a mix. We need both in our daily lives. Otherwise, we become toxic versions of masculinity (rational, linear, driven, doing) or femininity (intuitive, vulnerable, creative, being). Once again, Spider can teach us BALANCE.

I’ve written about this in Spiraling and then again in Blood and Money - Let it flow.

Beautifully woven, thank you!

Thank you for this walk along the threads of our spider kin’s lore… so beautiful!

I’m one of the weird ones who’ve always loved them… I grew up alongside the most venomous in the world, in my wee backyard in Sydney, others too, so magical.

I wonder if you might like the Native Australian story of Mararan and Marareen from the Spider Clan and how the spiders became two people (poisonous and not).